ETH reveals the secret behind perfect beer foam

Belgian Trappist beers keep their crown, lagers lose it quickly. ETH researchers show: The difference lies in a protein.

The head is not just an ornament, but the pride of every beer. In Belgian Trappist beers, the crown remains stable and creamy, whereas in lager it often disintegrates after just a few seconds. Researchers at ETH Zurich wanted to know why this is the case and, after seven years of intensive research, they have found a surprisingly simple answer: It's down to a single protein.

The protein is called LTP1 and behaves very differently depending on the brewing method. In lager beers, it remains stable and wraps itself around the foam bubbles like a protective shell. This keeps them in shape for a brief moment, then everything collapses.

More complex beers undergo a second or even third fermentation. This changes the protein: it cross-links, becomes more stable and keeps the foam longer. In the third fermentation stage, it finally breaks down into tiny fragments. They act like surfactants and have a water-loving and a water-repellent side, thus stabilising the bubbles. It is precisely this structure that gives Belgian Trappist beers their legendary resilient crown.

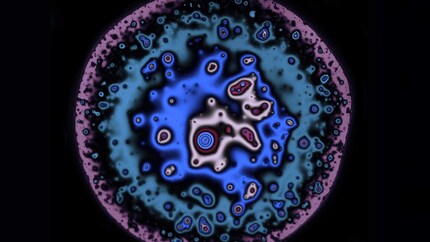

Source: Manolis Chatzigiannakis / ETH Zürich

But it's not just biochemistry at play, physics is also heavily involved. The so-called Marangoni effect is at work in these beers: differences in surface tension create currents that constantly supply new foam bubbles and stabilise old ones. This keeps the foam alive instead of simply collapsing. These theoretical findings are now being put to practical use in breweries so that in future not only Belgian Trappist beer but also other types of beer will shine with stable foam.

There is far more science between hops, yeast and foam than you might think. And anyone who looks at the crown of their next Belgian beer will now know that this is not just the art of brewing, but also protein physics at its finest.

I get paid to play with toys all day.

From the latest iPhone to the return of 80s fashion. The editorial team will help you make sense of it all.

Show all