Product test

Is the pricey Ghost of Yōtei Collector’s Edition worth it?

by Domagoj Belancic

Somewhere in between all those Steam downloads and day-one patches, we lost something important: the crackling pages of a freshly opened game manual.

We tend to romanticise the past: Kellogg’s Frosties tasted better when we were kids, comedies were funnier and music was more authentic. In short, everything used to be better. This is nonsense in most cases, very rarely standing up to any objective scrutiny.

There are exceptions, however, and I know one of them: video games used to have manuals, and that was better.

Video games are a young medium. Tennis for Two, the very first creation to be awarded the moniker of «game», was published in 1958. Sure, that was a while ago, but compared to movies (Roundhay Garden Scene, 1888) and books in the modern sense ( Twilight Diamond Sutra ca. AD 868), moving pixels are a recent leap.

Commercialisation didn’t even begin until the late 1970s. And when the first home consoles arrived in living rooms and children’s bedrooms, entertainment electronics were still uncharted territory. What we now intuitively understand as unwritten rules in gaming hadn’t yet been established at that time. It may sound surreal, but not all players automatically knew what to do when they slotted Super Mario Bros. into their NES in 1985.

The screen lights up and… what the hell are you supposed to do now? There’s a fat Italian with a porn-stache and something that looks like a deformed mushroom wiggling towards him. What now? No tutorial popup. No «press A to jump». Nothing.

Even what a controller should look like was still a matter of debate back then. There were joysticks, D-pads and all sorts of exotic faffery. In the mid-1980s, nobody knew what would ultimately prevail .

The logical consequence of all this: instructions for games. Manuals weren’t just a nice extra – they were essential for introducing the young medium to an inexperienced audience. This necessity led to something wonderful: developers began to realise that the manual could be more than just a sterile guide. It in itself could be art. Or at least something like it.

In 1994, I spent my summer vacation in Campiglia Marittima, Tuscany. Just like the year before. And just like the year before, I was dreading my two weeks in that town, five kilometres from the sea and with an average age of about 127.

My whining had an effect, and at the start of our vacation my mother surprised me with The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening for the Game Boy. Link’s first portable adventure was great, groundbreaking and epic, one of the best games for Nintendo’s cult handheld. However, there was one small problem: I had a Game Gear, not a Game Boy. I know, what a Shyamalan-tier twist!

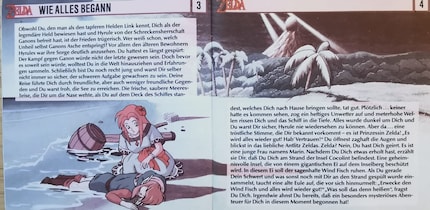

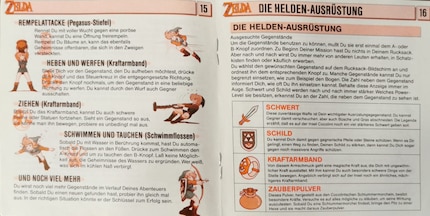

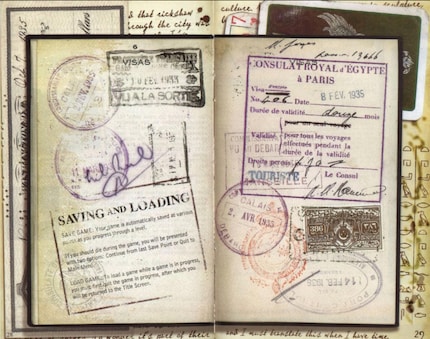

Once I’d worked through my disappointment and accepted I wouldn’t be able to get the cartridge to work in the rival console through sheer force of will, I settled for the next best option: meticulously studying the manual.

The world of Link’s Awakening remained barred to me, but the 30 or so pages in the manual allowed me a glimpse into my unattainable adventure. Detached from the actual game, I experienced my own tale, spun together from story snippets, item descriptions and character portraits.

Why’s Link stranded on Koholint? What’s the deal with that magic powder? Who’s that Mario lookalike? And why’s there straw everywhere? Three of these four questions were answered by my imagination, which would never have been possible without the manual.

This obsession probably isn’t a universal experience, but it illustrates how manuals were becoming an extension of games. They expanded the universe, gave context and turned a simple synopsis into a believable world.

The game and its manual were seen as a unit, a complete work of art. I could leaf through the pages endlessly, admire the illustrations and mentally prepare for what awaited me. A prelude, so to speak.

The instructions for Link’s Awakening were extravagant, but still classic compared to other releases. However, Nintendo has never been short on ideas, as demonstrated by the manual for F-Zero, which came with a complete comic.

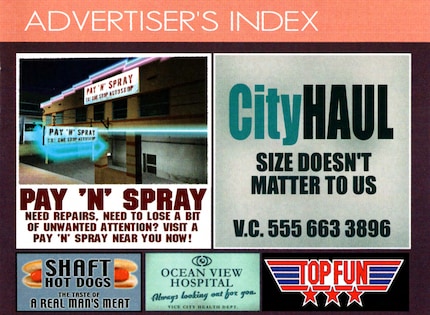

Lucas Arts, on the other hand, gave Indiana Jones and the Emperor’s Tomb a supplement based on Indiana Jones’ diary, and the GTA Vice City manual presented itself as a tourist guide, including an advertising page for various stores and brands from the game.

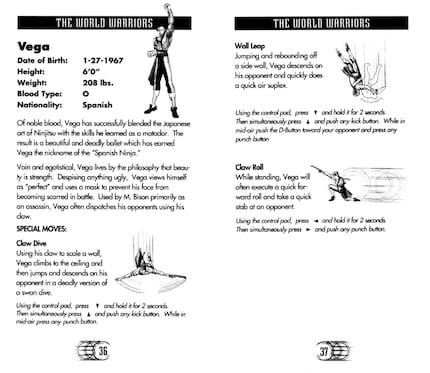

In addition, these manuals provided lore en masse. For years, I questioned why Vega wore an iron mask in Street Fighter II – until the manual told me that the cocky bastard was using it to protect his pretty face.

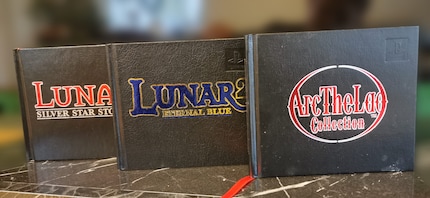

Working Designs deserves special praise. The American publisher saw manual creation as an Olympic discipline and regularly went the extra mile. Lunar: The Silver Star Story Complete, Lunar 2: Eternal Blue Complete and the Arc The Lad Collection all came with a manual in the form of a bound (mini) book. Hardcovers and all the trimmings. Aside from the expected tips and tricks, it also contained developer interviews, making-of stories, concept designs and sometimes even jokes and Easter eggs.

These manuals had better production value than some modern AAA titles.

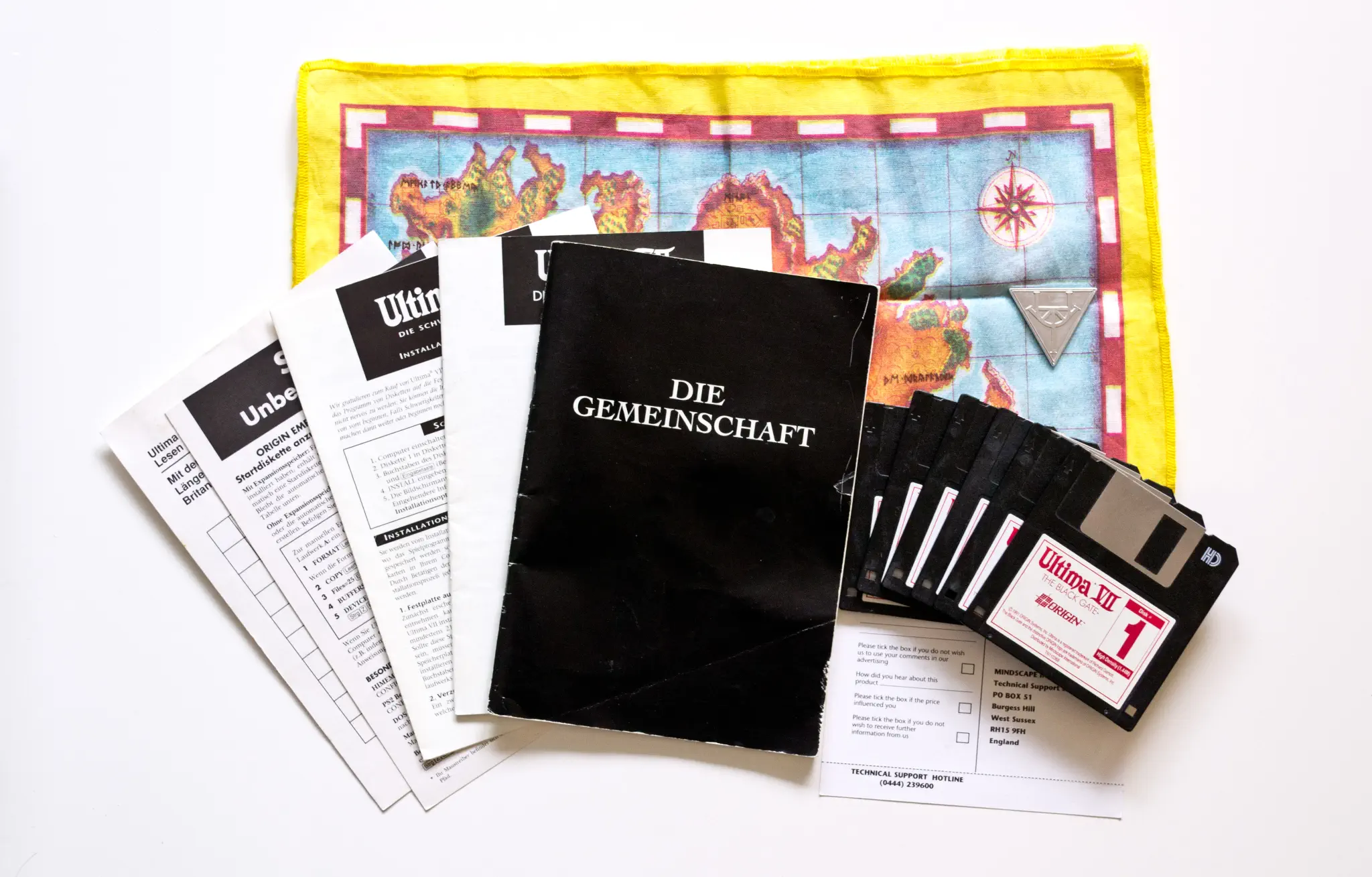

PC gamers had it even better. Those big cardboard boxes offered endless space for manuals the size of novels. Often they also contained fabric cards, keyboard overlays and physical gadgets that acted as copy protection.

The latter is a rabbit hole in itself and would go completely beyond the scope of this article, but perhaps one of my disk-wielding colleagues (come on Phil, you know you want to) would like to tell that story.

The point is, these boxes were little bags of joy. You weren’t just buying a game, you were buying an experience and unboxing was a ritual.

Generation 7 (PS3, Xbox 360, Wii) was the beginning of the end. In 2011, EA announced it’d completely dispense with printed manuals. Other publishers quickly followed suit. 40 pages became 20, then 10, and in the end all we were left with was a black and white scrap that looked like the manual for ibuprofen.

The 8th generation (PS4, Xbox One, Switch) finally closed the coffin. At best, regular releases still had an epilepsy warning or an online pass code included. Why? Simple: printing costs money, and in-game tutorials have taken over the task of manuals.

Lore, character bios and item descriptions also moved into the digital space, so there was simply no legitimate reason for a piece of paper any more. At least from the publisher’s point of view.

Now in 2025, the game manual is de facto dead. Limited Run Games, iam8bit and other boutique publishers who specialise in preserving physical titles sometimes include manuals with their releases. Larger publishers might add an artbook to their overpriced collector’s editions – for an extra 200 francs, of course.

Beyond that, however, the art form has largely disappeared today – and I think that’s a shame.

Digital is more efficient, no question, but something magical was lost: that feeling of leafing through the manual on your way home, the anticipation that built up when reading character descriptions and, to a certain extent, the (naive) illusion that video games are primarily made for our entertainment. Not just to finance the obscenely high bonuses of some sociopathic CEOs. Looking at you, Bobby Kotick.

All that’s gone now.

As I mentioned at the start, I’m not a believer in «everything used to be better». The gaming scene has never been more diverse, accessible and democratic than it is today. Just because we had to be satisfied with less back then didn’t automatically make things better.

But manuals were actually better. They were small works of art, a gift from developers to their fans and a physical connection to the virtual world. They turned a product into an experience and underlined the fact that games were always more than just a piece of entertainment software.

But as we all know, those doomed to die often live on against all odds – maybe this also applies to manuals. The vinyl renaissance has shown that people are willing to pay for feel and nostalgia. Cassette sales have risen again recently, and Polaroid cams never really went away anyway.

Maybe we’ll soon witness the comeback of game manuals. Or we’ll just have to get used to the fact that all things tangible will disappear eventually. «Attachment to an object always brings death to the possessor,» as French writer Marcel Proust once said.

Mind you, he never read the Link’s Awakening manual. So what can he really know?

In the early 90s, my older brother gave me his NES with The Legend of Zelda on it. It was the start of an obsession that continues to this day.

This is a subjective opinion of the editorial team. It doesn't necessarily reflect the position of the company.

Show all