Background information

Sharp PC-1403H: the legend lives

by David Lee

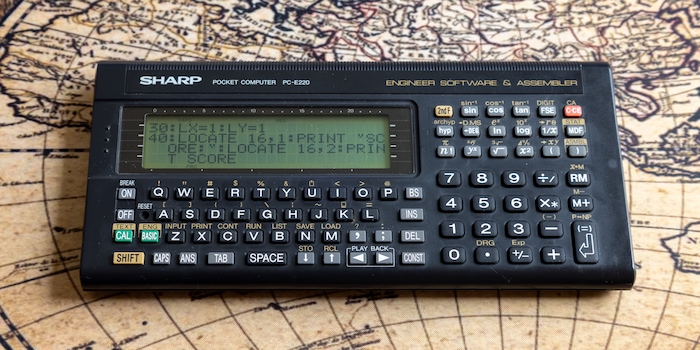

I just couldn’t resist making another game for an antiquated computer. This time, I used a Sharp PC-E220 calculator.

Last year, I dug out an old pocket calculator from my school days, programmed a game onto it and saved the program to a music cassette and computer. What a trip down memory lane.

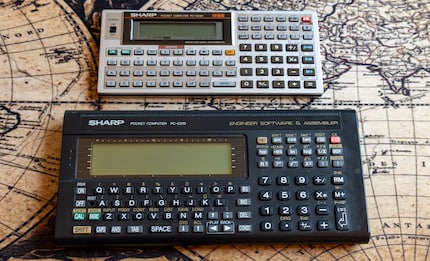

Since my last go, I’ve upgraded from a Sharp PC-1403H to a PC-E220. It has a much larger screen and can display four lines of text. Unfortunately, the LCD of the E-220 also has small spaces between the characters. This means there’s no continuous pixel grid, which makes it unsuitable for displaying graphics.

Transferring programs to the computer and back works the same way as with the Sharp PC-1403H, as they use the same interface. However, the E-220 doesn’t necessarily need backing up. Why? Because you can replace empty batteries without deleting the entire memory content. The E-220 runs on four AA batteries. Before changing them, you flip a switch so the power is temporarily supplied by a small button battery. This keeps the memory running during the battery swap.

Due to the four AA batteries the calculator needs, the E-220 is both larger and considerably thicker and heavier than the 1403H. Sizewise, it’s more Nintendo Switch than pocket calculator.

I enjoy programming like other people enjoy solving a Sudoku. However, the difference to a Sudoku puzzle is that you can get really creative with programming. And a large part of the programming puzzle is asking yourself what’s actually doable.

That’s why I like programming on old, simple machines. Their possibilities are limited, which gives you a clear framework. In this case, that means: Basic programming language, text-based, no colours, rudimentary sound. It’s worth pointing out, however, that there are a few differences compared to the 1403H. The multi-line screen allows you to move a figure in four directions. The Sharp PC-E200 can also output sounds in different heights and lengths. The PC-1403H can only manage a simple beep.

That’s why I decided to program a game of skill. After a few hours of tinkering, I’d done it. You can see the result in the video below, including a rare form of ray-tracing graphics. The aim of the game is to avoid the oncoming beams and reach the wall on the right. This earns you 100 points, then it starts all over again. After three mistakes, it’s game over.

Programming went smoothly and took about a day in total. The only challenge worth mentioning was making the game move fast enough.

The PC-E220 has a CPU with a clock frequency of 3 megahertz. That’s three times as much as the Commodore C64. I originally assumed that speed wouldn’t be a problem. I was wrong. You need to keep the game really simple to stop the movements coming to a standstill. It’s slowed down when there are a lot of beams and you have to keep making sure the figure doesn’t collide with one.

Therefore, I had to come up with a version that uses just four rays but is still interesting and difficult enough. Reducing the playing field from 24 to 10 squares was an improvement, but the game was still too easy. The decisive change was to stop the rays from popping up on random lines, but limiting them to the line on which the figure is.

The Sharp PC-E220 can also be programmed with Assembler, which would probably be faster. But I’m not familiar with it enough.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all